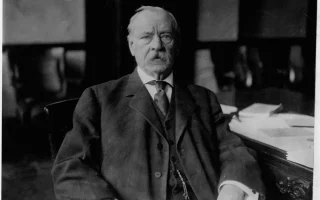

matechcorp.com – Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, is often remembered for his brief but eventful time in office, which lasted from 1921 until his untimely death in 1923. Harding’s presidency came at a pivotal moment in American history, just after the end of World War I, when the nation was grappling with the aftermath of global conflict, social upheaval, and economic challenges. In this context, Harding offered the American public a vision of “normalcy”—a promise to restore stability, peace, and prosperity after the tumultuous years that had preceded his election.

Though his presidency was marred by scandal and controversy, the promise of “normalcy” became the cornerstone of Harding’s appeal to the American people. His political platform and leadership style were grounded in the desire to return the country to a state of equilibrium, after the disorienting effects of the Progressive Era and the devastation wrought by the First World War. In many ways, Harding’s vision of “normalcy” captured the mood of the nation in the early 1920s: a yearning for peace, economic stability, and a retreat from international entanglements.

This article delves into the meaning of Harding’s promise of “normalcy,” exploring its implications for domestic and foreign policy, its resonance with the American electorate, and the lasting impact of this vision on American politics during the 1920s.

The Context of “Normalcy”: Post-World War I America

Warren G. Harding’s election in 1920 was a direct response to the chaos and upheaval of the preceding years. The United States had entered World War I in 1917, and the war had left an indelible mark on the country, both economically and socially. The cost of the war was astronomical, and although the U.S. emerged victorious, the nation was left with deep scars. The war had strained the U.S. economy, created a political climate of suspicion and fear, and left many Americans questioning their place in the world.

At the end of the war, President Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic vision for a post-war world was encapsulated in his Fourteen Points, which called for the establishment of the League of Nations and a new world order based on diplomacy, collective security, and self-determination. However, the American public was not enthusiastic about Wilson’s internationalist agenda. Many Americans, exhausted by the war and wary of further foreign entanglements, desired a return to domestic priorities. The failure of the U.S. Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations highlighted the growing isolationist sentiment in the country.

Simultaneously, the nation was struggling with a series of domestic challenges. The war had spurred rapid industrialization, and while this brought economic growth, it also led to social dislocation. The labor movement was gaining momentum, and there were widespread strikes and protests across the country as workers demanded better wages and working conditions. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had fueled fears of communism and socialist uprisings in the U.S., leading to the Red Scare of 1919-1920, a period of intense anti-communist sentiment and political repression.

Against this backdrop, Harding’s promise of “normalcy” struck a chord with the American electorate. His vision represented a desire for a return to stability—political, economic, and social—a time before the upheaval of war and the ideological battles that had characterized the Progressive Era. Harding’s call for normalcy resonated with a public that was weary of reform movements, international intervention, and political radicalism.

Harding’s Campaign for “Normalcy”

Warren G. Harding’s presidential campaign in 1920 was centered around his call for a return to “normalcy.” His platform stood in stark contrast to the more progressive policies of the Wilson administration, which had championed the expansion of federal government power and active involvement in world affairs. Harding’s message, delivered with great clarity and simplicity, promised a break from the complexities of the war years and a return to a more traditional, less interventionist approach to governance.

Harding’s campaign slogan, “Return to Normalcy,” effectively captured the mood of the nation. After the ideological battles of the Progressive Era, the strains of the war, and the challenges of the postwar world, many Americans longed for a sense of peace and stability. Harding’s vision was one of economic prosperity, lower taxes, less government regulation, and a withdrawal from the global stage. He promised to focus on domestic issues, reduce government interference in the economy, and restore a sense of order to the country’s political and social systems.

Harding’s emphasis on normalcy also reflected a rejection of the wartime presidency of Woodrow Wilson, whose idealism had failed to win over a significant portion of the American public. Harding portrayed himself as a man of moderation, a political figure who would bring a sense of common sense and reason back to government. His rhetoric resonated especially with those who were skeptical of the progressive reforms that had marked the previous decade and those who were disillusioned with the results of World War I.

In his campaign speeches, Harding focused on themes of healing and reconciliation. He emphasized the need to restore calm in the aftermath of the social unrest and divisions that had marked the postwar period. Harding was careful not to alienate any particular group, appealing to both conservatives and moderates, as well as business leaders and workers. His message of unity and his promise of a “normal” America helped him connect with voters from all walks of life.

Domestic Policy: Economic Prosperity and Conservative Values

Once Harding assumed the presidency, his commitment to “normalcy” was reflected in his domestic policies. He worked to reduce the influence of the federal government in the economy, advocating for tax cuts, a reduction in government spending, and a general retreat from the aggressive regulatory stance that had characterized the Progressive Era.

Tax Cuts and Economic Growth

One of Harding’s first acts as president was to implement tax cuts, particularly for high-income earners and corporations. Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, was a key advocate of supply-side economics, which held that lowering taxes would spur investment, increase productivity, and ultimately lead to greater tax revenue. Harding and Mellon believed that reducing the tax burden on businesses and the wealthy would stimulate economic growth and lead to a more prosperous America.

The tax cuts, along with a reduction in government spending, helped to usher in a period of economic expansion in the 1920s. The United States experienced rapid industrial growth, a booming stock market, and rising wages for many Americans. The so-called “Roaring Twenties” was marked by increased consumer spending, technological innovation, and a sense of optimism that was in part a result of the economic policies of Harding’s administration.

Deregulation and Business Interests

In line with his vision of normalcy, Harding worked to roll back many of the regulatory policies put in place during the Progressive Era. His administration favored pro-business policies that prioritized the interests of large corporations and sought to reduce the reach of federal agencies in regulating industries. Harding appointed businessmen and conservative figures to key positions in his cabinet, emphasizing the importance of free-market principles and minimal government interference.

The business-friendly climate of Harding’s administration helped to foster economic growth, but it also contributed to growing income inequality, as wealth became concentrated in the hands of a few. While the stock market boomed and industries flourished, the benefits of this growth were not equally distributed, and the disparities in wealth would later contribute to the economic instability that marked the end of the 1920s.

Labor and Social Issues

While Harding was generally sympathetic to business interests, he also had to address the growing labor movement in the country. The postwar years saw significant labor unrest, with numerous strikes and protests by workers seeking better wages and working conditions. Harding’s response to these issues was relatively moderate. He believed in the importance of balancing the interests of labor and capital, and he worked to maintain social order while not fully embracing the more radical labor demands of the time.

In some ways, Harding’s policies reflected a more conservative approach to social issues. For example, Harding opposed the expansion of civil rights for African Americans and did not actively promote significant reforms in the area of racial equality. However, he did speak out against lynching and racism, albeit in a limited way. Harding’s administration also began to focus on limiting immigration, as concerns about the impact of immigration on American society gained traction during this period.

Foreign Policy: Isolationism and the Washington Naval Conference

Harding’s foreign policy was largely shaped by his commitment to isolationism, a key element of his vision of normalcy. Harding believed that the United States should focus on its own domestic concerns rather than becoming entangled in international affairs. This was reflected in his decision to reject the League of Nations, which President Wilson had championed, and to pursue a more cautious and non-interventionist foreign policy.

One of Harding’s most significant foreign policy achievements was the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-1922, in which the major naval powers—including the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, and Italy—agreed to limit the size of their naval fleets in an effort to prevent an arms race. The conference was a symbol of Harding’s desire for peace and stability in the international arena, as well as his commitment to avoiding further military entanglements.

Harding’s isolationist foreign policy was popular among many Americans, particularly those who were weary of the interventionist policies of the Wilson administration. However, this approach also left the U.S. more distant from international affairs, and in the years to come, the rise of global tensions and the failure to address economic instability would prove to be a challenge for future administrations.

The Legacy of Harding’s “Normalcy”

Warren G. Harding’s presidency was short-lived, as he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1923, less than three years into his term. However, his promise of “normalcy” and his vision for the country had a lasting impact. The economic policies that Harding put in place set the stage for the booming prosperity of the 1920s, but the focus on business interests and limited government also contributed to the inequality and excess that would eventually lead to the Great Depression.

Harding’s legacy remains mixed. While his presidency brought a sense of peace and stability after the war, it was also marred by scandal, particularly the Teapot Dome scandal, which would tarnish his reputation for years to come. Yet, despite these blemishes, Harding’s vision of normalcy had a profound impact on the trajectory of the United States during the 1920s, and his presidency marked a shift away from the more progressive policies of the past toward a more conservative, business-oriented approach to governance.

In conclusion, Warren G. Harding’s promise of “normalcy” captured the spirit of an American public that longed for peace, stability, and economic growth after the disorienting effects of World War I and the Progressive Era. His presidency marked a transitional moment in U.S. history—one that offered a brief respite from political and social upheaval but ultimately set the stage for the challenges and crises that would follow in the coming decades.